A woman flings herself into the air on a secluded beach, her red dress lifting from the force of that leap, its color a vibrant splash against the blue sky and endless horizon. She is so exuberant that she seems to defy gravity. Any moment now, those graceful arms might carry her away beyond where we can see. Phoebe Boswell’s Liminal Deity could be a portrait of joy and exhilarating freedom. But that dress: it is both elegant and harrowing, made of either feathers or flesh. Its shade of red hovers on the edge of darkness. Those could be feathers whipping in the wind. It could also be tender flesh, disintegrating. It is flight in motion. It is a wound exposed. The shadow that seems to dance in front of this woman, could it be trying to flee? So much in this work is a suggestion: is this joy, or is this pain? It is impossible to know from her expression, the face is rendered featureless. Liminal Deity, like all of Phoebe Boswell’s art, dares us to give up our certainties. It challenges us to travel across uncharted territory, not for the sake of safety, but for a more complicated and layered understanding of all that can exist at once. In that space, Boswell asserts, lives possibility and even freedom.

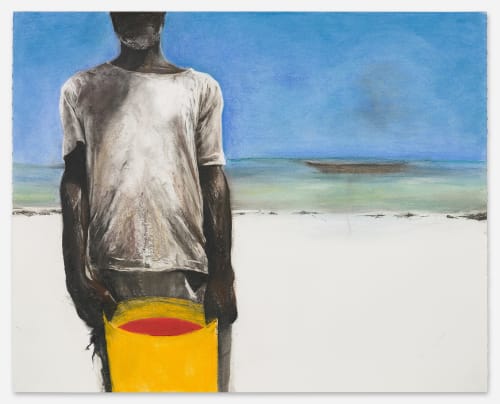

This work is part of Phoebe Boswell’s exhibition, “Liminal Beach”, at Berlin’s Wentrup Gallery. In these portraits of fishermen and other residents of a coastline that echoes the shores of East Africa, the ocean is a moody and powerful presence, less a backdrop to life than a steady companion. It beckons as one solitary woman stares into the horizon in To Know the Weather. It is stark and foreboding as a group gathers their nets in Bless the Boats. The ocean gleams, crystalline and inviting, as two men talk in All Possible Everything. It seems to rise and embrace the young men in Future Ancestors. The ocean: eternal and mercurial, sheltering and threatening.

A hint of its power is made evident in the curation of “Liminal Beach,” where a shimmering, silvery reflective wall covering both mirrors the paintings back to the viewer and places us firmly within the line of sight. We are seeing. We are the seen. The lines between observer and subject, between the ocean and the city, between mirage and reality, blur. The horizon expands, endlessly. In this new series of bold, sensitive paintings – seen for the first time in Berlin -- Boswell continues to push us further into that unstable, uncomfortable terrain where real change and inspiration reside.

Phoebe Boswell is an interdisciplinary artist with breathtaking range and talent. Her art moves fluidly across several mediums - drawing, video, animation, sound, interactivity, performance, writing, and painting – all of it in the service of questions about who we are and how we see/are seen, about what we embody physically

and what we contain within us in that invisible territory of the imagination, the voice, and the spirit. Born in Nairobi, Kenya and raised in the Arabian Gulf, Phoebe now lives in the UK and spends time in her family home in Zanzibar. It is a diasporic existence, consisting of many worlds and languages, the landscapes of her childhood separated by bodies of water which have witnessed migrations and homecomings, becoming both graveyards and paths towards a new life. Her work springs from that tension, inspired by bodies bound by flesh and bone, and those made of water.

Boswell’s 2019 Wake Work series, consisting of drawings in graphite on black paper, includes portraits related to three Black African immigrants, Emmanuel Chidi, Idy Diene and Pateh Sabally, who died in separate incidents fuelled by anti-immigrant backlash in Italy. These faces – defiant and curious, enraged and grief-stricken, dignified - rise to the surface in certain angles of light on that black paper. It is difficult to see them clearly without shifting the gaze, without moving our own body to accommodate their image. These three men, their loved ones, and the community who came out to advocate on their behalf, hover in front of the viewer, ghostly but present against that black expanse, defying distance and time, swallowing light. In this, as in other bodies of work, Boswell provides us with a visual language for something that still feels unspeakable. She constructs for us a map of loss, an architecture for containing the ruin, and in the process, she insists that we do more than look. She asks that we move towards her subjects, that we turn to the angle of light, and in that way, become witnesses to that liminal space where the dead not only speak, they scream. Her work – mesmerizing and compelling – demands that we do not walk away. And like the best of art, it offers us shelter until we are strong enough to listen.

What does it mean to draw a person? To gaze at a person? To truly see a person? The earthly body, after all, is the first point of contact between strangers. A face, naked and defenseless. Full of nuance and testimony. A body, loaded with a history of meanings. So vulnerable to the reactions and assumptions of others. Its own fragile landscape. A body: so tender to the touch that every glance towards the other is also a sacred oath gesturing towards care. To recognize the tenderness of a body that is also Black, that is also African, that is also the carrier of histories of oppression and enslavement, that is also the evidence of defiance and new freedoms – this is the space within which Phoebe Boswell’s art resides. Care is a basic tenet. Healing is both a promise and a demand.

Look with me: An African man walks along the shore in Zanzibar, his facial features hidden in shadow, his body small against the vast horizon of the ocean (I Dream of a Home I Cannot Know, 2019); twelve Black figures drawn in charcoal on coffin-sized boxes stand with their backs to the viewer, so individual and unique it is as if we are looking at their faces, too (Transit Terminal, 2014/2020); Black couples, including mothers and their child, in a swimming pool, one teaching the other how to swim while their heads stay above water and out of frame (dwelling, 2022 | And I Love You For All Your Splashing: An Ongoing Emergence of Nature, 2023). In each of these and other works, Boswell extends the call for care to encompass the entire body. A body, as in Liminal Deity, that is audacious in its expressions and radical in its freedoms. A body that does not have to show its face to insist on care and healing. A body that is loved.

– Maaza Mengiste